زیادہ تلاش کیے گئے الفاظ

محفوظ شدہ الفاظ

کِھسیانی بِلّی کَھمبا نوچے

جسے غصہ آرہا ہو وہ دوسروں پر اپنی جھلاہٹ اتارتا ہے، بے بسی میں آدمی دوسروں پر غصہ اتارتا ہے، شرمندہ شخص دوسروں پر اپنی شرمندگی اتارتا ہے، کمزور کی جھنجھلاہٹ

چَمَنِسْتان

ایسا باغ جہاں پھول کثرت سے ہوں، ایسی جگہ جہاں دور تک پھول ہی پھول اور سبزہ سبزہ نظر آئے، گلزار، گلستان، باغ، پھولوں کا قطعہ، سبز کھیت

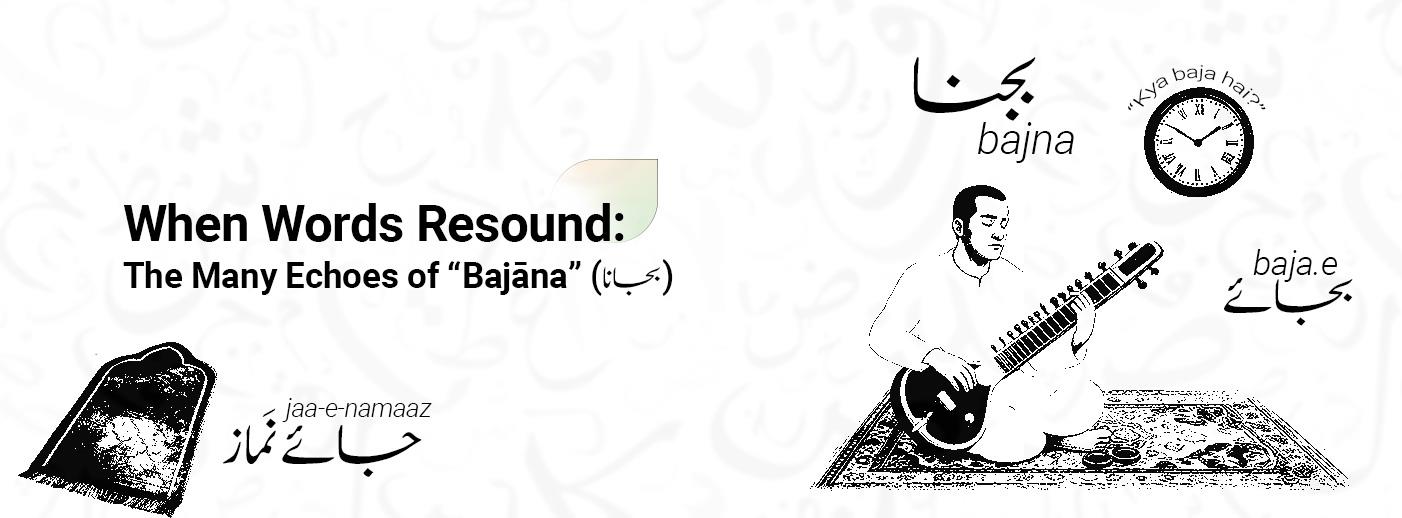

When Words Resound: The Many Echoes of “Bajāna” (بجانا)

If I ask you, “What does bajāna mean?” — you might laugh and say, “Who doesn’t know that? It means to play — like bajāna sitar, bajāna tabla!”

And you’d be right. In Urdu, بجانا (bajāna) means:

• to play a musical instrument,

• to perform or execute music,

• to beat a drum or gong,

• to strike a bell or clap hands (taali bajāna – تالی بجانا).

Even a woman’s anklets bajti hain — they chime softly as she walks.

The Sanskrit Connection — Sound as Speech

The story of bajāna begins deep in Sanskrit, from the root वद् (vad) — meaning “to speak.”

From this ancient root evolved words related to utterance, expression, and resonance — acts of giving voice.

So when Urdu says bajāna, it doesn’t merely mean “to make a sound”; it carries an older echo — to make something speak.

The drum, the sitar, the anklet — all become speaking bodies of rhythm.

When Time Itself Rings

Now, if someone asks, “Kya baj rahā hai?” (کیا بج رہا ہے), you might think they mean, “Which tune is playing?”

And you wouldn’t be wrong.

But then we also say, “Kya bajā hai?” — meaning “What’s the time?”

Why this overlap between sound and time?

Because in earlier times, people heard time before they could see it.

Before watches and clocks, hours were announced by bells, gongs, and conch shells in towns and villages.

Thus, bajna (بجنا – to ring, to sound) became a way of marking time itself.

As in this verse:

رات رخصت ہوئی بجتے ہیں گجر آگے چل

ہونے والی ہے تمنا کی سحر آگے چل

raat rukhsat hui bajte hain gajar aage chal

hone waali hai tamanna ki sahar aage chal

Night departs — the bells of dawn are ringing ahead,

Move on, for the morning of longing is about to rise.

Here, gajar (گجر) refers to the pre-dawn ringing — the call that announces daybreak.

And how effortlessly Urdu weaves languages together!

The Sanskrit word gajar (गर्ज, meaning call or ringing) pairs with the Persian dam (دم, breath or moment) to form subah-dam (صبح دم) — at the break of dawn.

The Persian Connection — Place, Propriety, and Precision

While bajāna and bajna belong to the Sanskrit world of sound and expression, words like bajaa, bajaa.e, and jaa-ba-jaa come from Persian, where the meanings shift entirely.

In Persian,

• jaa (جا) means place, position, or occasion, and

• ba-jaa (بَجا) means in place, proper, appropriate, right.

“Ba” (با) means with, by, for, or in.

So when we say “aap ne bajā farmāyā” (آپ نےبجا فرمایا), we are not talking about sound at all — we mean “You have spoken correctly” or “You are right.”

From this base, Urdu developed several graceful expressions:

• (bajā.e) بجائے — in place of, instead of

بجائے سینے کے آنکھوں میں دل دھڑکتا ہے

یہ انتظار کے لمحے عجیب ہوتے ہیں

bajāe sīne ke āñkhoñ meñ dil dhaḍaktā hai

ye intizār ke lamhe ajīb hote haiñ

Instead of beating in the chest, the heart throbs in the eyes —

These moments of waiting are strange indeed.

• (jaa-ba-jaa) جابجا — here and there, scattered, everywhere

Like scattered notes of music — the sound and meaning dispersed across space.

• (hukm bajā laana) حکم بجا لانا— to carry out an order.

• (adab bajā laana) ادب بجا لانا — to show respect humbly, often by placing a hand on the chest or bowing slightly.

Let us, in passing, mention one more word — jaa-e-namaaz (جائے_نماز), meaning the mat or carpet on which prayers are offered.

In Urdu, it is commonly shortened to jaanamaaz (جانَماز).

Between Sanskrit’s word and Persian’s jaa,

Urdu found its own music —

a language where meaning, rhythm, and grace all ring true.

Delete 44 saved words?

کیا آپ واقعی ان اندراجات کو حذف کر رہے ہیں؟ انہیں واپس لانا ناممکن ہوگا۔